Around 18 months ago I wrote a piece examining the reported provenance for a Cycladic head sold through Christie’s New York in April 2022. According to the information supplied by Christie’s, the head was initially owned by the Swiss antiquities dealer Heidi Vollmoeller who acquired it in the 1960s. Vollmoeller held the head for roughly the next 15-20 years, until it was sold to the Merrin Gallery in New York in the 1980s (and then onto other anonymous owners). Unsurprisingly, however, I found issues with this provenance offered, and suggested that it had at least been partially fabricated and that the head was likely owned by the dealer Nicolas Koutoulakis.

Following that blog piece going live, Judith Barr kindly drew my attention to an addendum published by Pat Getz-Gentle (née Getz-Preziosi) in 2008. In this, Getz-Gentle reveals that she had additional background for 104 Cycladic figurines (or parts of figurines) that were included in Peggy Sotirakopoulou’s ‘The “Keros Hoard”: Myth or Reality?’ Using the designations A-1, A-2, A-3, B, and C, Getz-Gentle provides, in descending levels of certainty, additional provenance information for these figurines based on records available only to her, to reinforce her belief that these pieces belong to the so-called ‘Keros Hoard’.

Within this ‘addendum’ the head sold by Christie’s in 2022 (no. 156 in Sotirakopoulou 2005) is assigned by Getz-Gentle to her A-1 category. According to Getz-Gentle, figurines in this category were “identified as belonging to the [Keros] hoard that I saw on visits to N. Koutoulakis from 1968 through 1983. I have photographs of these pieces that I took myself or that were sent to me, at my request, by Koutoulakis.” Without information to the contrary, then, it appears certain that this head was in the possession of Koutoulakis (as hypothesised) at least as late as 1968 and this information was conveniently left out of the provenance provided by Christie’s. With this new information, one wonders just how reliable the remaining provenance is …

—

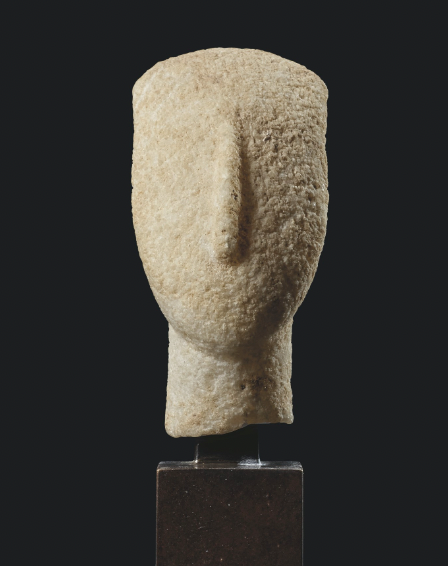

Following this discovery, I began to look for other heads from Cycladic figures sold in recent years by Christie’s. In doing so, I came across one (lot 27: of the Early Spedos type) put up for auction on the 8th of December, 2021 (fig. 1: sold for £22,500). As with the head discussed in the previous post, this piece also has a curious provenance. According to the listing, this Cycladic head was part of the infamous Erlenmeyer collection “as per [the] 1970 invoice”; it was then sold to the dealer Ugo Donati in 1970 (note the pre-1972 provenance), and then at some point acquired by Dr Giancarlo Ligabue. Presented, here, is a seemingly clear custody chain, supposedly with supporting documentation (not that it is made available on the listing), that establishes clearly that the head was circulating the market prior to 1970 when Marie-Louis Erlenmeyer apparently parted ways with it.

Yet some points require clarification. First, it is well-established that the Erlenmeyers bought their Cycladic material from the aforementioned dealer Nicolas Koutoulakis. Assuming this holds true here, there is, then, at least one link missing from this provenance chain. Secondly, the link with the Erlenmeyer collection is odd. That the Erlenmeyers collected Cycladic material is well-known, and it is frequently noted in publications that they acquired a large portion of the problematic ‘Keros Hoard’ when it first began to surface (see, for example, Sotirakopoulou 2008). This material was apparently acquired in the mid-1950s from Koutoulakis, and studied between 1968 and 1975 by Pat Getz-Gentle (née Getz-Preziosi)*. In a 2008 article, Getz-Gentle (p.300) recounts her first impressions of the Erlenmeyer collection noting that “Although this material included several interesting works, for the most part it was composed of the sort of bits and pieces, of scholarly interest only, that Koutoulakis was happy to dispose of. There were few heads and no fragments of unusually large works” (emphasis mine). It seems odd that a head, particularly when uncommon within the collection, would have escaped Getz-Gentle’s notice. Even if one accepts that Getz-Gentle missed the head and Marie-Louis Erlenmeyer sold it in 1970, it is still seems odd that it was not brought to the attention of Getz-Gentle in her subsequent visits to see the Erlenmeyer collection.

That the head is unpublished is also odd—this remains true even if we ignore its absence from Getz-Gentle’s works. The Erlenmeyers were clearly proud of their collection and on several occasions published parts of it themselves. In 1965, five years before the head in question was supposedly sold to Donati, they published Von der frühen Bildkunst der Kykladen, which featured several of the more valuable pieces of Cycladic sculpture they owned. This included two heads, several largely complete bodies, and the one almost complete figurine, all of which were kept in the collection until Marie-Louise Erlenmeyer eventually sold them through Sotheby’s in 1990 (the heads were lots 135 & 136). Noticeably absent from this publication is the head sold through Christie’s in 2021. In fact, the Christie’s auction, as far as I can tell, is the first time this head has surfaced, let alone been associated with the Erlenmeyer Collection.

The link with Ugo Donati deserves further mention too. A quick search on Google tells us that Ugo Donati died in 1967, three years before he supposedly acquired this piece from the Erlenmeyer collection. It seems likely that what is really being referred to here is the antiquities dealership that was owned by Donati, Donati Arte Classica, which continued to operate after his death. If this is the case, then Christie’s reference to ‘Ugo Donati’ may be a simple typo. However, other antiquities sold through Christie’s, and other auction houses, have been accompanied by provenances that included Donati and made this distinction clear. In October of 2019, a terracotta head was sold through Christie’s and the provenance notes that, at some point (no dates are provided), the sculpture was “with Donati, Arte Classica, Lugano.” Likewise, in July last year (2023), a pair of legs from a Cycladic figurine, were sold through Christie’s and apparently were once “with Pino Donati, Arte Classica, Lugano, September 1970” before being purchased by “Dr Giancarlo Ligabue (1931-2015),” from whom the seller acquired them (given the provenance for the head, this provenance also raises questions: for example, did Pino Donati also acquire the legs from the Erlenmeyers?). If the reference to Ugo Donati for our Cycladic head is just a simple typo, then it serves as yet another reminder of the lack of care auction houses frequently give to provenances.

Of course, it is possible that the head sold through Christie’s was sold by Marie-Louis Erlenmeyer in 1970. If this head did indeed come from the Erlenmeyer collection, then this has potential implications for our understanding of the so-called ‘Keros Hoard’ and its modern history. It suggests that the Erlenmeyer collection was larger (by at least one head) than previously thought and perhaps held more significant sculptural fragments than the “bits and pieces” Getz-Gentle saw. If this is true, then one wonders how much larger this collection was and if any other pieces were sold off by the Erlenmeyers prior to the famous 1990 auction of part of their collection at Sotheby’s. Moreover, inclusion in the Erlenmeyer collection is often used as a justification of sorts for including Cycladic sculptures in the problematic assemblage of material labelled ‘the Keros Hoard’. If this head did come from the Erlenmeyer Collection, then one wonders if it was once part of the corpus of material the Erlenmeyers purchased from Koutoulakis. If so, should it also be considered part of the Keros Hoard? Should this be the case, then it would seem that the hoard, the size and veracity of which is still debated (e.g. see the three articles discussing the hoard in the AJA volume 112.2, 2008), is larger than previously thought. Unfortunately, however, once again, due to a lack of market transparency, we are left in the dark. Without the opportunity to consider the documentation that supposedly supports the provenance provided by Christie’s (and rule out the possibility of forgery à la Getty Kouros (or any number of other equally fitting examples)), or the extensive photo archive Getz-Gentle possesses, these issues will likely never be resolved.

Richard Bott (@RichardBott7)

*In a chapter published in 1983 (The ‘Keros Hoard’: Introduction to an Early Cycladic Enigma p.37), Getz-Gentle claimed that she was first able to study the Erlenmeyer collection in 1975: “In 1968 I made a rapid survey of some 70 figure fragments still in the hands of the original owner[, Koutoulakis]. In 1975 when I returned for a more thorough study of the group I was shown an additional 97 pieces. That part of the material in the Erlenmeyer Collection, numbering roughly 140 pieces, I was also able to study in 1975.” Later, however, in the article from 2008 (p.300), she stated that “I also met Marie-Louise Erlenmeyer (now deceased) in 1968 and was able then, and on several later occasions, to examine the part of the [Keros] hoard that she and her late husband had acquired from Koutoulakis.” Why she reports two widely different points of examination is unknown.

**Unfortunately, a full copy Sotirakopoulou’s excellent monograph, The Keros Hoard”: Myth or Reality? Searching for the Lost Pieces of a Puzzle, is not freely available online. Likewise, I was unable to find an openly accessible version of Getz-Gentle’s aforementioned chapter, ‘The ‘Keros Hoard’: Introduction to an Early Cycladic Enigma’. In Antidoron: Festschrift für Jürgen Thimme zum 65. Geburtstag am 26. September 1982, edited by D. Metzler, B. Otto, & C. Müller-Wirth (pp.37-44).